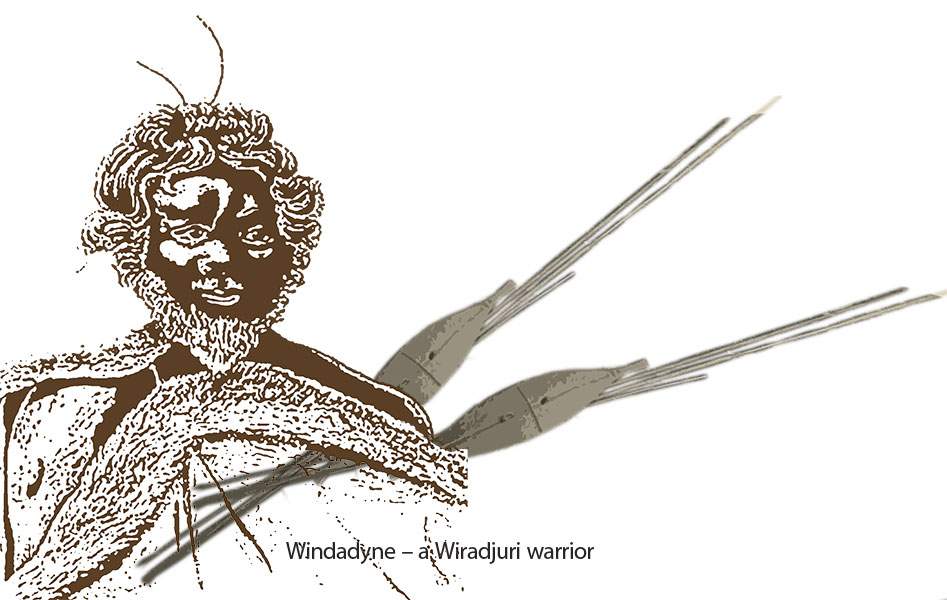

Wiradjuri country is the land of the ‘three rivers’, the wambool (Macquarie), the galari (Lachlan) and the marrambidya (Murrumbidgee).

This is the largest territory of any language group in New South Wales. It extends from the Blue Mountains west to Nyngan, and from Gunnedah in the north to Albury in the south.

Perhaps 12,000 people were living in Wiradjuri country in 1788. They maintained their country and culture by travelling throughout their land, honouring sacred connections and kinships and undertaking ceremony.

A central Wiradjuri belief is a creation unified by Baiame, who is all-powerful, all-knowing and eternal. The Wiradjuri wore possum-skin cloaks and carved trees at burial grounds and birthing sites.

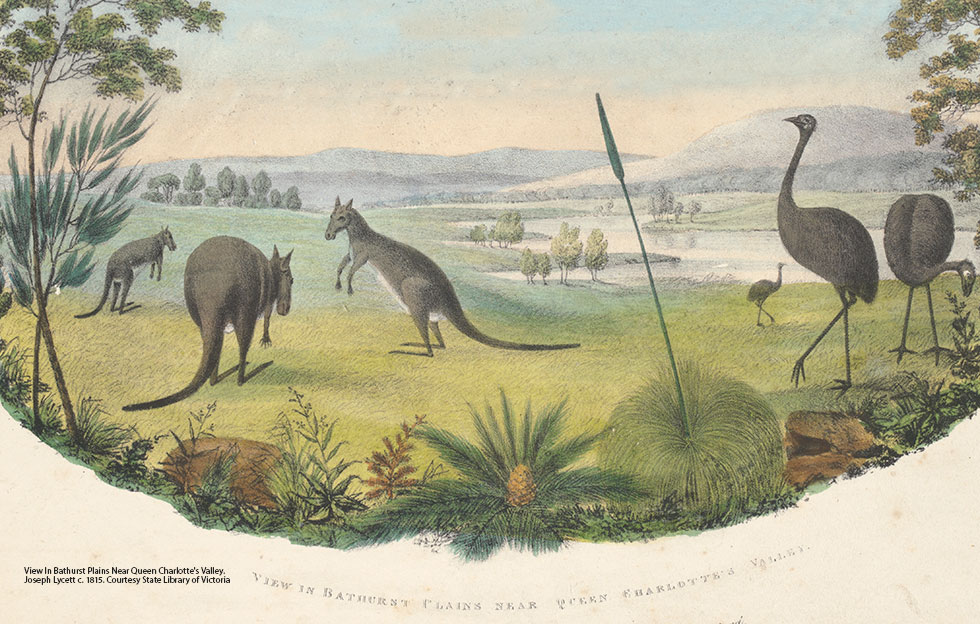

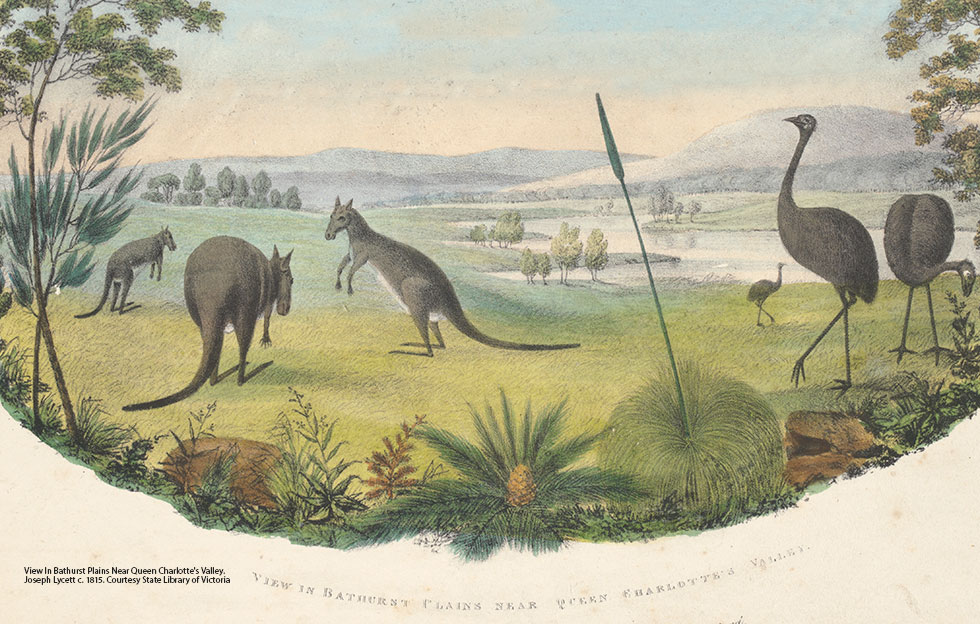

Extended family groups moved seasonally around the productive Wiradjuri river basins to manage and gather food.

The streams provided abundant fish, turtles, yabbies and shellfish. On the surrounding woodland plains the people hunted emu, possum, goanna and kangaroo, and collected wattle seeds, tubers and many other plant foods.

Wiradjuri country provided everything the people needed. Life changed slowly, guided by the circle of seasons and a rich and complex culture that united the land, the people and all life.

But after many thousands of years the Wiradjuri had to adapt quickly when a strange new people came into their land.

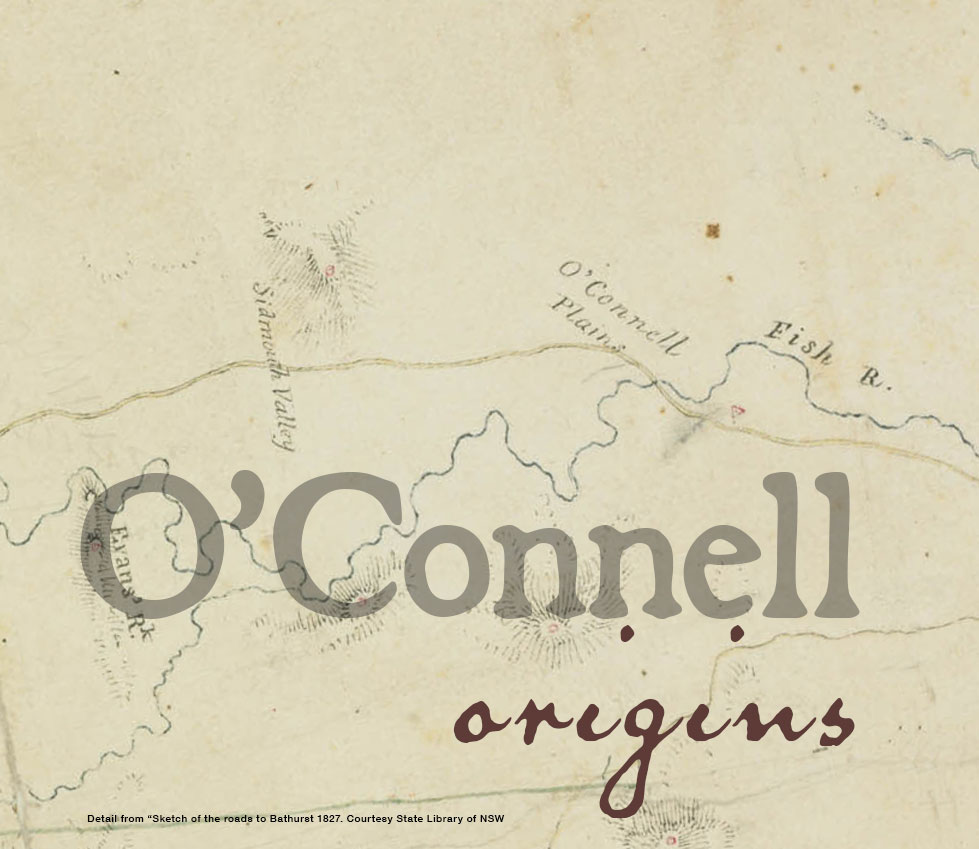

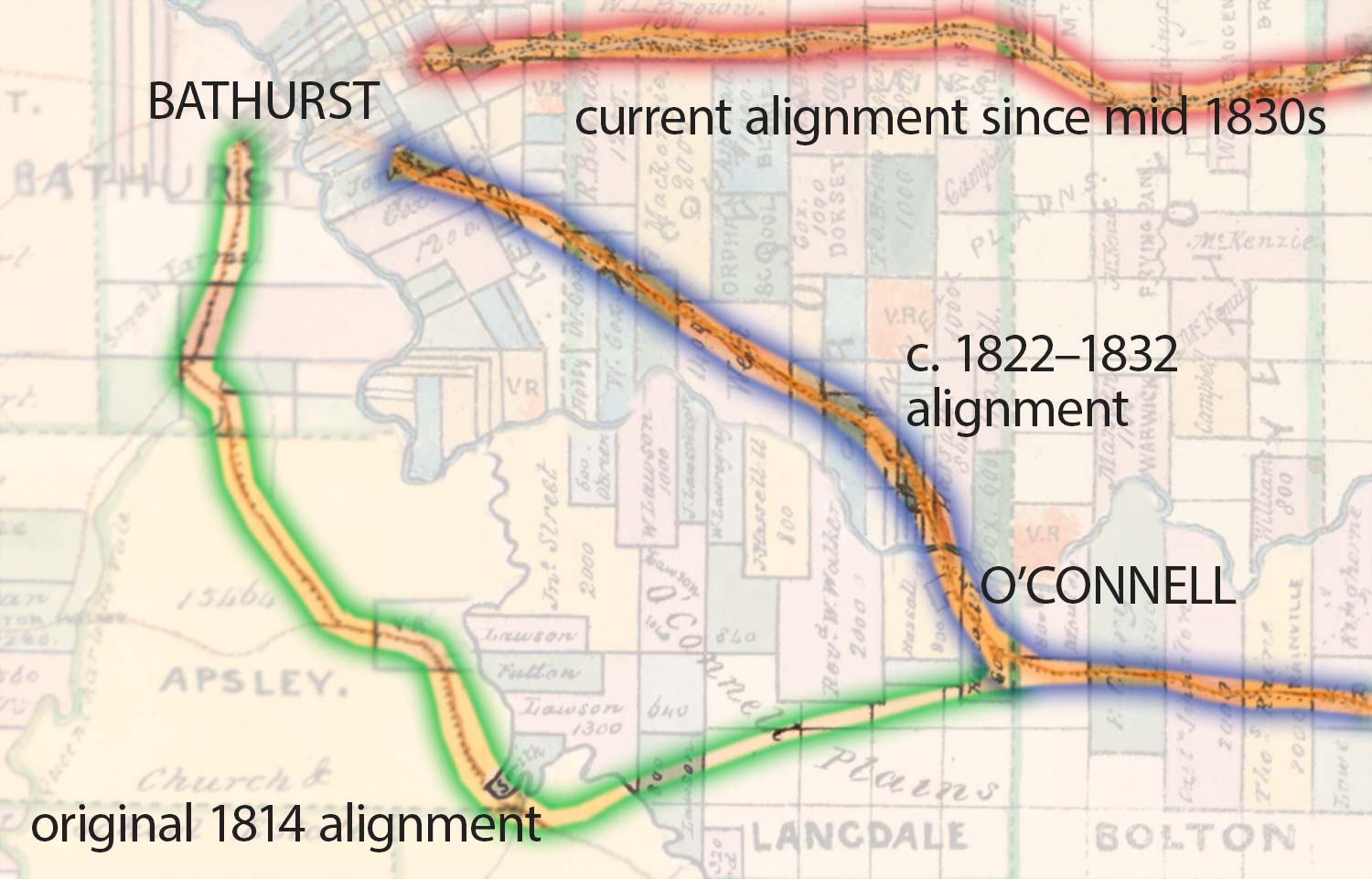

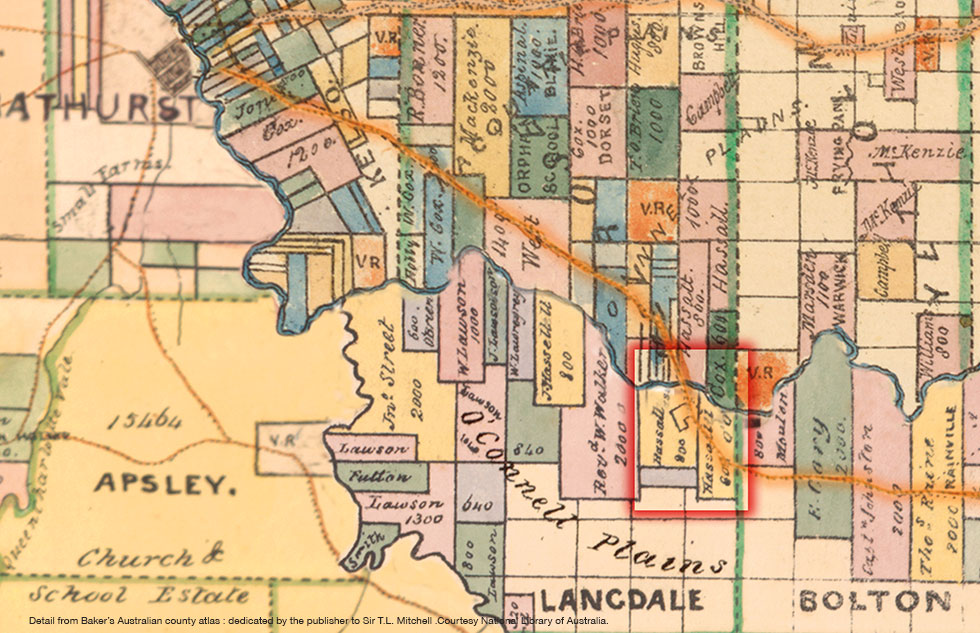

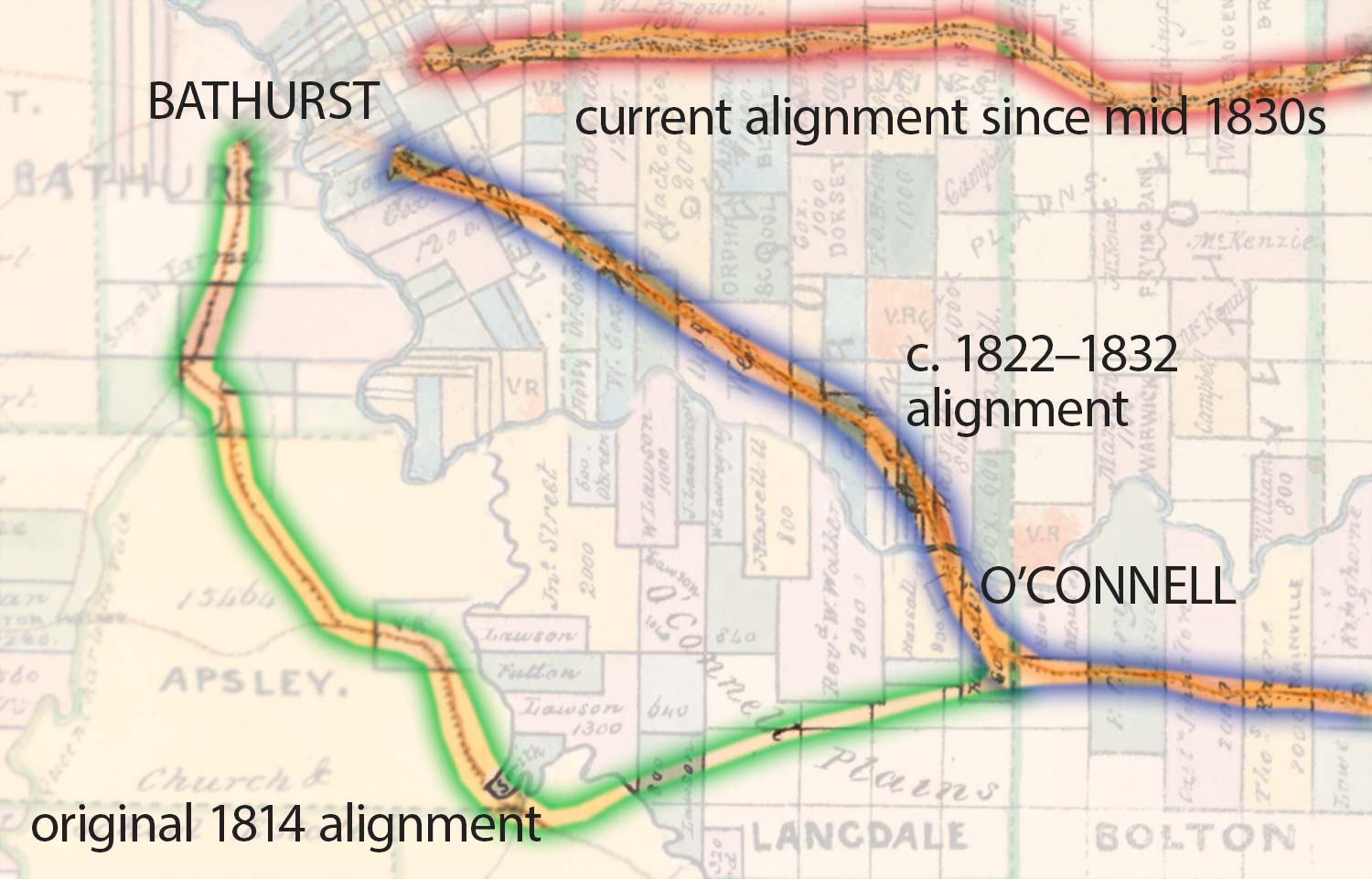

Around the same time as 800 acres of land on the eastern edge of the O'Connell Plains beside the Fish River was formally granted to Reverend Thomas Hassall by Governor

Brisbane in June 1823, the main Bathurst Road was diverted to create a more direct route through Hassall's new holding.

This road relocation was to set Hassall's property apart from his neighbours in terms of its relevance in the surrounding landscape. Its location on the flat side of the river at the Fish River crossing positioned it to develop into a roadside destination of note in the following decade.

Even when the present day highway alignment was created in the mid 1830s, the old road through O'Connell and along the Fish River continued to be used by bullock teams who valued the numerous watering points it offered along the way. This in turn facilitated the ongoing development of the village in the years leading up to the discovery of payable goldfields in the Bathurst region in 1851.

Daniel Roberts owned the Mill Cottage, which stands on the northern side of the Fish River and was built of random rubble by convicts in 1826. He also built the first water-driven flour mill in 1837 nearby to process locally-grown wheat and was granted the first publicans license for O’Connell Plains on 3 July 1833. Roberts

established his Plough Inn on the northern bank in 1833 along with a store and a blacksmiths shop. The Plough Inn was one of only 13 inns established before 1835 on the western

road between Sydney and Bathurst.

Rev. Thomas Hassall was the first clergyman to establish a place of

workshop (Anglican) at O’Connell Plains.

As his continued appeals to Bishop Broughton that a church be built at the village were refused due to a lack of funds, he sold his land at Sydney and purchased land in the southern part of O’Connell Plains. Hassall also acted as a local tenens for about 12

months conducting services in a temporary building at the Kelso village during the absence of the

Rev. John Espy Keane of the then new Kelso parish. Rev. Hassall subsequently

built at his own expense a rough mud building known as the Salem Chapel in 1831. This was located at the junction of Beaconsfield Road and O’Connell Road and no longer

exists.

A police presence was established in O’Connell from 1828 and Constable William Merrick was

the first policeman appointed followed by Constable Samuel Taylor in 1834.

Their duties frequently involved the apprehension of escaped convicts. O’Connell’s Post Office first opened on 14 August 1834 and for many years was located in the store at the junction of Beaconsfield Road and O’Connell Road.

Mail between Bathurst and O’Connell was conveyed using a one-horse vehicle twice a week through a mail contractor appointed in 1846. This mail contractor was John Roberts, son of Daniel Roberts, innkeeper of the Plough Inn. Two years later, an innkeeper and well-known mail contractor of Bathurst, Henry Rotton, had secured the same contract.

Horse races were first held on Daniel Roberts’ property behind the Plough Inn in 1849 and it

appears that they were celebrated annually on 26 January.

The first day school to open at O’Connell was likely by the Church of England faith in connection

with Salem Church. The first appointed school master was William Jones and

some 30 children were enrolled some days after the opening of the day school.

O’Connell experienced significant growth during the gold rush period of the 1850s-60s and by 1870s was well established with a settlement of over 300 people.

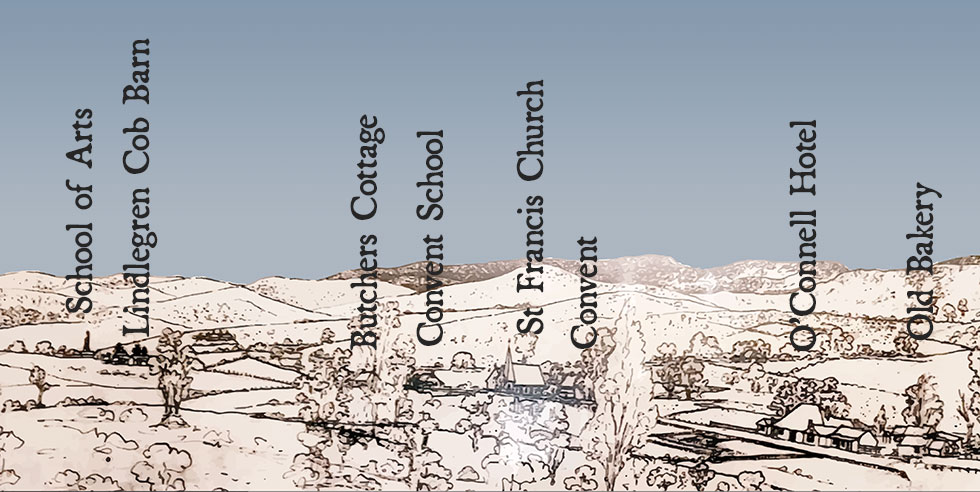

Many of the buildings remaining today were built during this period, including the St Francis Catholic Church (1866), St Francis Convent (1867), St Joseph’s Convent School (1878), St Thomas Anglican Church (1866), St Thomas Rectory (1877), O’Connell Hotel (1870), O’Connell Public School (1876), the Butcher’s Shop (1876), the Old School of Arts (1870), the Butter Factory and the Police Station. It was during the 1860s that ‘Plains’ was dropped from O’Connell Plains and in 1866, O’Connell was formed into a separate parish.

The sketch of the road through O'Connell shown below dates from 1913. It is one of a range of historic mementos on display today in the O'Connell Hotel.