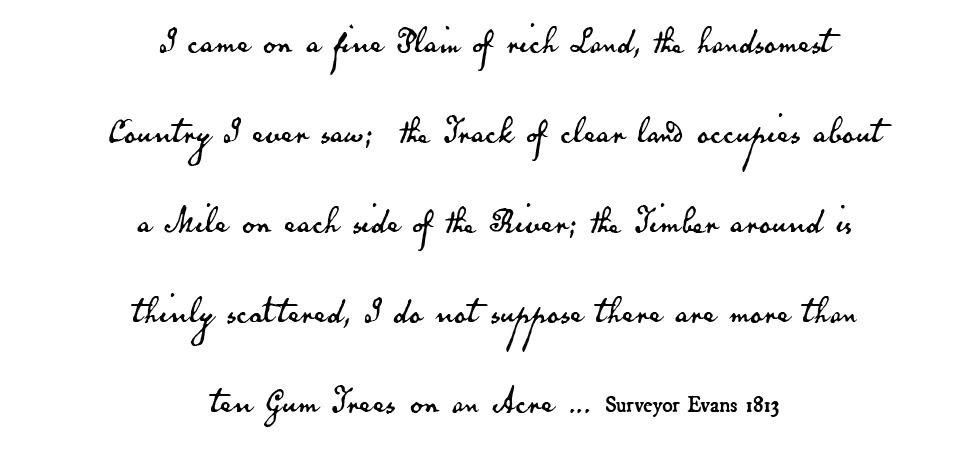

When Surveyor Evans came across the tract of Country he named O'Connell Plains after the colony's Lieutenant-Governor Maurice O'Connell in 1813 he ranked it as the "handsomest Country" he'd ever seen.

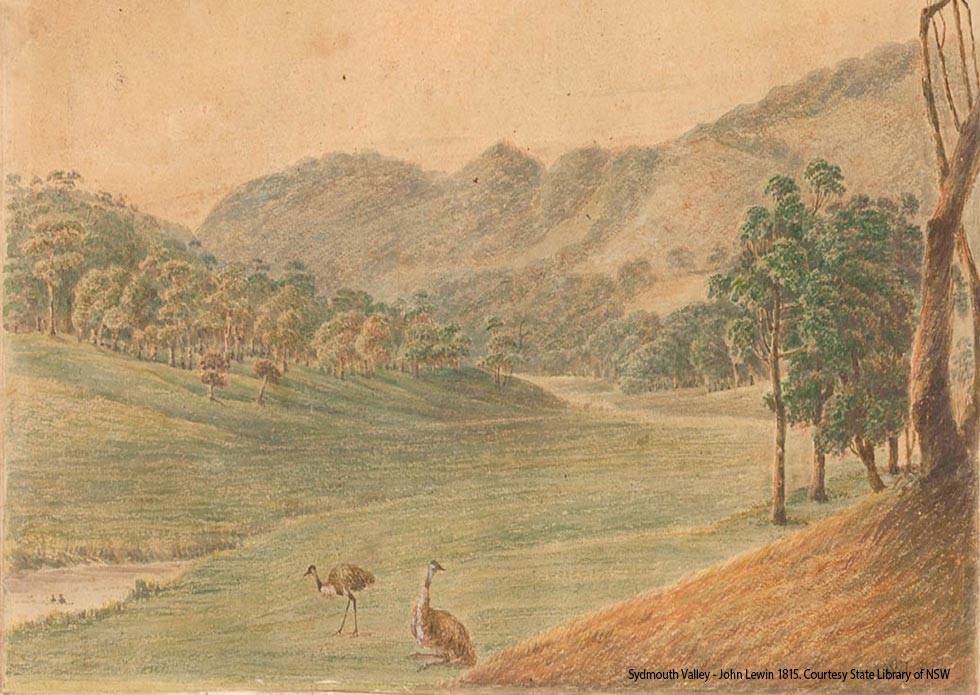

Soon after this in 1815, some of the local views were recorded by the artist John Lewin when Governor Macquarie travelled along the newly built Coxs Road to Bathurst. Lewin's view of the nearby Sidmouth Valley to the east of O'Connell captures the swathe of riverside open land that Surveyor Evans had described.

Looking at this image it's easy to image how tempting it would have been to take advantage of the rich alluvial soils as a source of building materials. Indeed, in the same year as the Reverend Thomas Hassall took up his new 800 acre land grant here on the southern banks of the Fish River, the Sydney Gazette was arguing that earth buildings were an ideal construction approach to be used in parts of the country which may be thinly wooded such as the plains around Bathurst.

By the time this article was published in June 1823, Thomas Hassall may have already constructed a sod walled, earth house on his property at O'Connell. Hassall's son was later to write that:

As there was no Church or parsonage, he erected a house upon his land, which after the usual fashion in the Bathurst district then, consisted of sod walls and grass thatched roof. The sods were cut out with a spade in squares, at right angles from the surface and laid upon another with the grass side downwards. The soil was a black clay. When the walls were up, the outside was smoothed down and stuccoed with lime, so that they looked as if built of brick or stone.

It appears though that the Reverend Hassall was only a brief occupant of this original cottage - the precise location of which today is unknown. Having taken up residence here in January in 1826, he was joined by his wife and children in May, and left in 1827 for Denbigh in the Cowpastures.

Active management of the property however continued in his absence and it was later in that year of 1827 that one John Barker was paid £17 for ‘putting up a barn and £2.10 for putting up a fence at the bottom of the garden’.

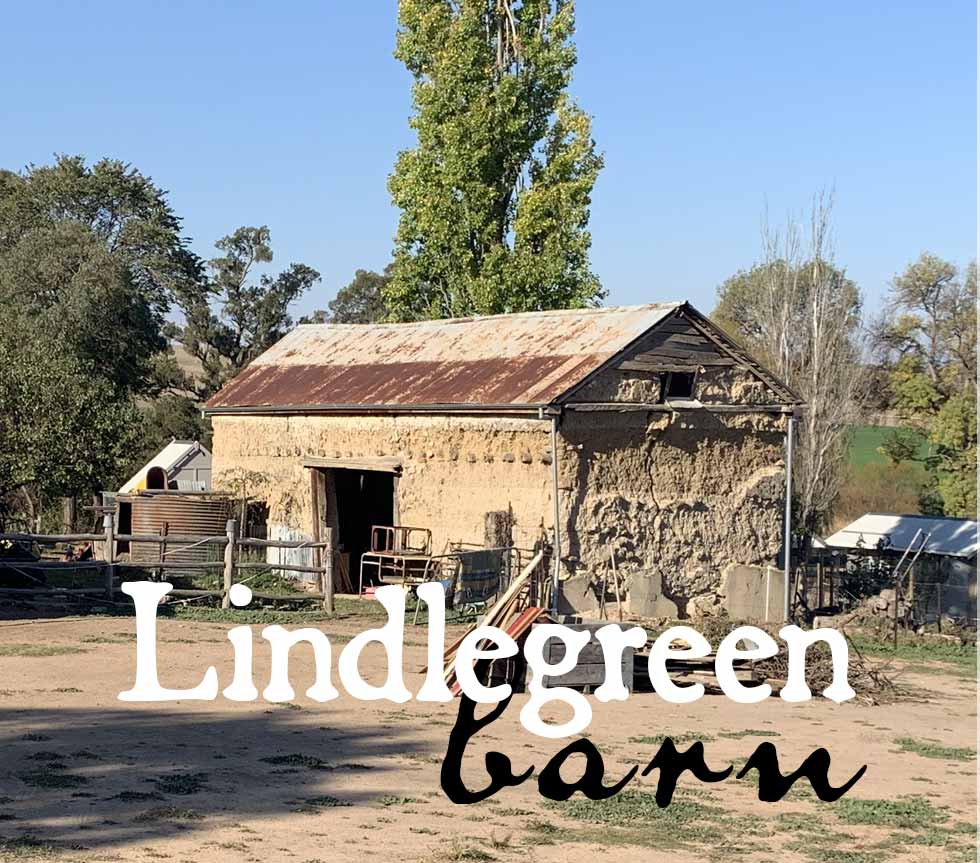

The barn that Barker built in 1827 is today the same one we see today before us at Lindlegreen where it is recognised as the oldest standing mud construction in Australia.

The Barn has been described wrongly as pise. The two to three feet courses and straw mixture depict a different story.

The straw in the cob is clearly visible in both the mud-rendered finish and in the areas of wall where the render has come away. This confirms the technique is cob, not pise as it has sometimes been described.

The external walls, which are eighteen inches thick at the bottom, batter to twelve inches at the top in courses that average about two feet high.

Considering the wall is not all that thick for its height, it suggests the cob was laid with the help of shuttering to maintain a constant batter. All of the buildings on site are of twelve inch thick cob, built on stone footings to prevent rising damp.

The construction process of cob buildings differs greatly to other building techniques mainly as cob is applied wet.

‘…pise is gravelly loam rammed dry without draw, while cob is a moist pug mix of clay and straw, laid in layers by hand…Traditionally cob was laid by hand in courses in a fairly wet state, in manageable blocks about the size of a large pillow. …each layer had to allowed to dry out before going higher. This meant that each rise of about three feet could not be built upon without a drying period of about three weeks, and then only if the weather was fine…It was finally painted with a whitewash, typically made of equal parts of melted tallow and slaked lime. Ideally cob walls were built on footings of stone or brick, but numerous examples were built straight on the ground.’

An interesting part of the barn’s construction is a layer of black pitch painted underneath the lime wash on the exterior walls.

This provides waterproofing to the building. There is little evidence of the black pitch left, however some traces can still be seen underneath the eaves.

The Lindlegreen Barn represents an example of one of the very few surviving cob buildings in NSW. It is also one of the oldest of this building type in Australia.

The photo below highlights the layers of earth construction that can today be easily discerned in the building.